Woody Allen’s career has been so long, so varied, and so influential that conventional summation seems fatuous. So I’m not really going to do it. That’s Thing #1.

Thing #2 is this: Let me declare right now, before God and Ingmar Bergman, a bias towards what Woody calls his “early, funny stuff.” Take the Money and Run, Bananas, Play It Again Sam, Sleeper, Love and Death, Annie Hall, Manhattan: That run of films defined its era like nobody since Preston Sturges, and maybe Chaplin. That’s the Woody that speaks to me—which puts me, and most of the comedy people I know, in a bit of an awkward position. On the one hand, who doesn’t admire Woody for wanting to keep producing? On the other, the fact remains that we’ve traded a comic genius for a maker of genial foreign films which happen to be in English.

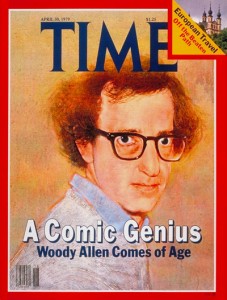

So perhaps the most important thing to say about Woody Allen is what he was. From around 1965 to 1980, if you were urban, educated, literary, intellectual—or merely wished to be any of these things—Woody Allen was God. Every movie was an event, to be watched over and over, memorized, quoted. He achieved a kind of prominence that’s simply impossible in a 1000-channel world. Only Monty Python came close, and if Python was The Beatles, Woody Allen was Bob Dylan. He was that important, that singular, that revered. He would’ve broken Twitter.

Early Woody Allen is pure shtick—Woody the person was no more a sex-starved schlemiel than the real Harpo Marx was a mute. But it was a perfect updating of the kind of craft-focused comedy that Allen grew up with. As that vogue subsided in favor of verité, Allen didn’t miss a beat. The stammering standup that did “The Moose” in 1965 had, by 1972, eased into an onscreen persona perfectly tuned to the college crowd. Part of this is Allen’s fundamental nostalgia; if you pick up his first collections of humorous essays, Getting Even (1971), Without Feathers (1975), and Side Effects (1980), you’ll see that every piece is utterly Allen, while at the same time inextricably linked to old-school types like Robert Benchley and S.J. Perelman.

Woody’s time on Olympus peaked with Annie Hall (1977) and Manhattan (1979), two must-views for anybody serious about comedy. That these critical raves were followed by Stardust Memories (1980), a Fellini homage that ends with the Allen character being shot by a deranged fan (six weeks before Mark David Chapman did it for real), speaks volumes, even though Allen denies it was autobiographical. From the moment of that screen murder, Allen’s comedy has never been the same. More mature? Perhaps. More nuanced? Sure. But less funny.