Some writers live on via their writing, in syllabi and the bottom of beach bags; is there any doubt that, say, Kurt Vonnegut or Joseph Heller will still be read in 40 years? (I’ll make sure of this personally if need be.)Â Others, perhaps the majority, must borrow immortality through the people they influence.

S.J. Perelman is definitely the latter—his was a language-besotted mind, complex in syntax and rich in vocabulary, the product of a word-dominated culture that winked out around 1963, if it had ever really existed at all. In this era of the instant 140-character celebrity joke, Perelman’s writing is so demanding, so wide-ranging in its influences, so goddamned old-fashioned that it seems amazing that this was once mass-market humor. And it’s not merely a question of age, either: A Wodehouse story from 1930 can recall the rhythms of a sitcom; a Benchley essay from 1925 can sound exactly like a blog post. Not so with S.J. Perelman.

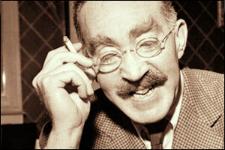

The writer himself had no illusions about his uniqueness: “Before they made S.J. Perelman,” he famously wrote, “they broke the mold.” Yet in spite of, or perhaps because of, this high degree of difficulty he remains  a favorite of comedy folk. Jaded palettes prefer strong, odd flavors. Steve Martin and Woody Allen are both noted Perelmaniacs. And so Perelman lives on, in the occasional homage-casual…not to mention whenever TCM rebroadcasts Horsefeathers. (Perelman and Groucho Marx were often conflated in the public mind, something which irritated both men.)

Perelman came along near the tail-end of that great explosion of American humorists—we’ll say it started with Ring Lardner, continued on with Benchley and the Algonquins, reached its mainstream high water mark with James Thurber, and began to peter with Perelman. Not surprisingly, his background mirrored those others: first, time on the college humor magazine, brief starvation in New York followed by a stint at one of the big comic weeklies. And then, like Benchley and Parker before him, Perelman headed west to Hollywood to fame, fortune, and incredible bitterness.

Perelman’s difficulties with the Marx Brothers (he co-wrote Monkey Business and Horsefeathers) are well-known and, given what he became, entirely predictable. Perelman’s value as a writer is primarily the uniqueness of his prose. He simply wasn’t cut out to write in other people’s voices; what most of today’s comedy writers do for a living was anathema to him. Luckily, The New Yorker was in full flower, and he buzzed happily about that field of clover for nearly fifty years. Though he wrote plays and even won an Oscar, Perelman’s legacy was the essays—he rather characteristically called them “feuilletons,” and if that makes your head hurt a bit, best to move on. Â