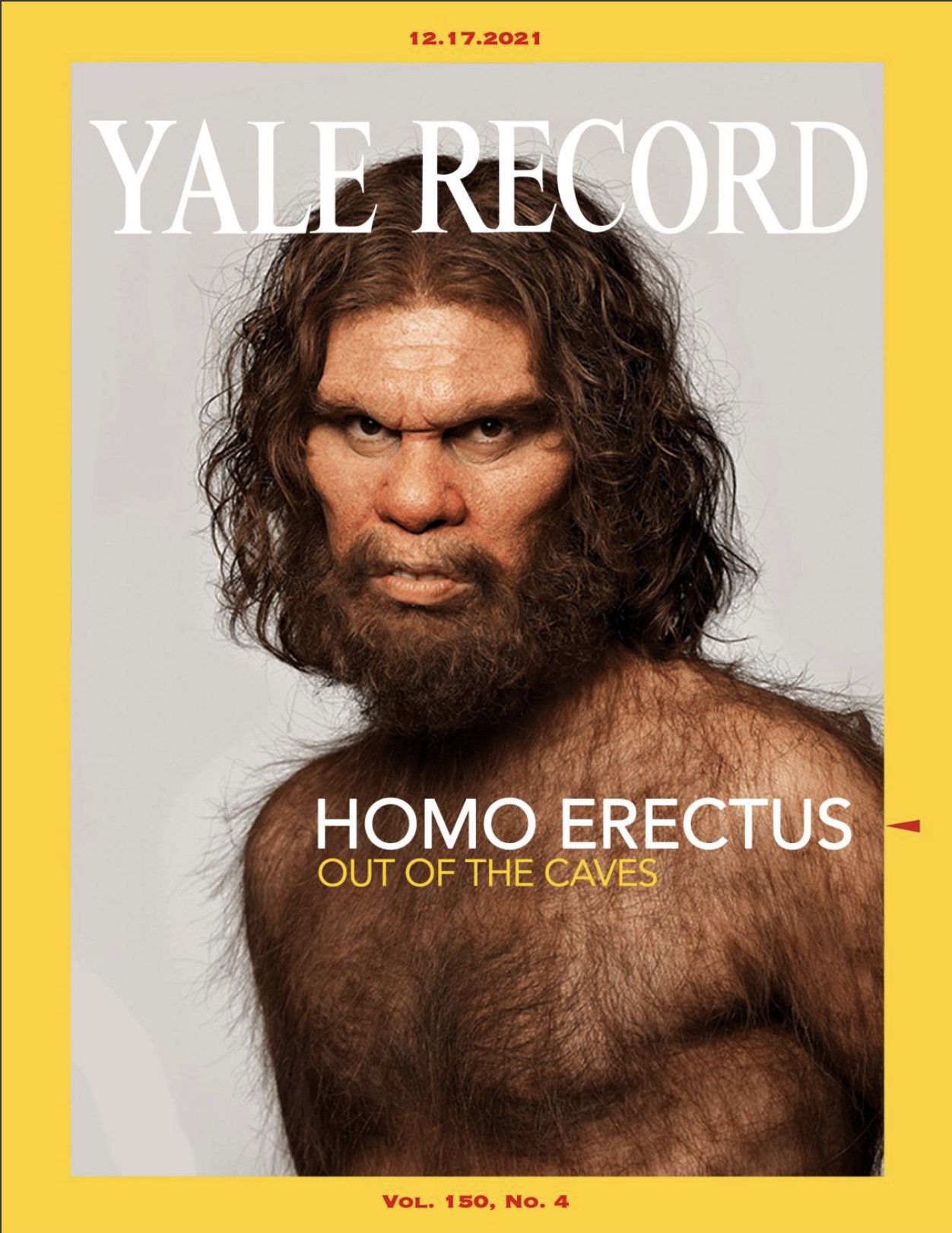

The torrent above whips and whirls, but in the cave there is fire. The flickering glow within casts its shadows upon the cliff face: a roiling mass, figures, limbs. Behind the pounding of the rain, a high melodic hoot wends its way through the turbid air. Come close, dear reader. Watch, listen. This is where the homo erectus sing.

* * * * *

These days, most people view animals as a commodity. Rhino horns are ground up and used in sex drive pills for joyless married couples in New England suburbs. Thousands of tons of hoof, the strongest material known to man, are used every year to build nuclear bunkers and above-ground pools. New Yorkers pluck live pigeons from telephone poles and peel them like bananas for a midmorning snack. There’s monkey blood in hand lotion. There’s chicken in nuggets.

We’d do well to treat the creatures of the earth with a little more respect. After all, we humans were once creatures ourselves. There was a time not too long ago when we ate bugs, climbed trees, and said things like “ooh ooh ah ah” unironically. But the early men, apes, man-apes, and ape-men that walked the earth in days of yore are gone. Millennia after their grisly demise, the telling of their history falls to us.

Three million years ago, the earth was a very different place. Giant sloths roamed the forests, hunting medium-sized sloths that nourished themselves on the nutrient-rich pelts of tiny sloths. Instead of buildings, there were trees. Instead of swimming pools, there were rivers and lakes. A sun-dappled canopy shaded a dank and cozy underbrush where gross bugs made merry. Humanity was just a twinkle in the eye of a ratlike primoid, desperately trying to prove evolutionary viability to its pack by braining cave frogs with jagged rocks.

One million years later, the sloths were long dead, killed by a meteor they couldn’t outrun. From the rubble came homo erectus. They left the cave and faced the light of day. They befriended the intelligent fish people who had evolved simultaneously in a nearby tributary. They built the first huts out of mud and sticks. They built the first fires out of mud and sticks. They tried eating mud and sticks but that didn’t work so instead they hunted animals with mud and sticks.

Over thousands of years, they learned to work as a team. They invented leaders and jail. In one voice, they sang a ballad that spanned the generations. The contours of their simian hoots grew subtle and defined, and language was born. Each word was a poem, each sentence a song. With this new tool in their arsenal, homo erectus quickly drove the fish people to extinction. They felled megafauna and built tambourines from hulking femurs. When their leaders hogged the femur tambourines, they put those leaders in jail.

Life was not easy, but it was good. Many homo erectus thrived in the harsh conditions of the Pleistocene. Many more ate poisonous mushrooms, fought grizzly bears, or wandered into the frozen north and were lost to time. Fire proved a fickle ally. In their hubris, they torched whole forests, and evolved hairlessness over the millennia to assuage the ever-present smell of burning fur.

After another million years, a new hominid emerged. Homo neanderthalensis quickly dominated the prehistoric scene with their big brains and stubby arms. Their tools were sharper, their huts more spacious, and their jails more carceral. When they built fires, they always kept a bucket of sand nearby.

The erectus coped as well as they could. Some began hoarding mud to stymie the newcomers’ supply lines. The most immature ones sent gifts of feces that they insisted were a regional delicacy. A particularly dejected contingent returned to the cave and devolved over the next million years into the common garden snake. Still, erectus and the neanderthals lived in relative peace, and both species kept mostly to themselves. A few interbred to produce my ancestors, the Irish, and skirmishes ended in a matter of minutes because neither party had invented cruelty yet.

The good times couldn’t last forever, of course. Three hundred thousand years ago, a tribe called Homo sapiens marched out upright from a glen to the south. We crafted primitive guns from mud and sticks, and drank fermented sorghum juice that made every day feel like Christmas in July. The cruelest of us would ask oblivious hominids to spell “ICUP,” and then cackle with glee when they revealed that they hadn’t invented the alphabet yet.

The rest is prehistory. We devoured erectus and neanderthalensis or drove them north to icy graves. We hacked down forests with bronze tools and built enormous statues of triangles. We wrote, drew, and digitally designed the National Geographic Issue of the Yale Record to further humiliate our furry friends. We killed the creature within and without. Nothing could stop Man’s avarice. Nothing but His destruction.

Still, hope glimmers behind a pale blue veil. Somewhere beyond the tundra, maybe, homo erectus crouches at the heart of a glacier. He dines on fish and sleeps on a bed of seal pelts, safe from our machines and machinations. Someday we will be gone, one way or another, and maybe then he will return. Until then, read this magazine.

It’s got jokes in it.

* * * * *

The torrent above whips and whirls, but in the cave there is fire. Deep below the icy cathedral, blue-tinged shadows dance on the frozen sheets as they have for generations. Come close, dear reader. Watch, listen. Somewhere, hidden, the dance continues. Deep in the cave, homo erectus sings his mighty song.

—J. Wickline

Editor in Chief